Reflections and Learnings from the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Our early efforts with the EFFORT trial were truly enlightening. As the first site to enroll patients, we worked with the CERU team to make the data fields and resources more intuitive. As a former INS site, we understood the scope of the variables needed, but a number of factors are different with EFFORT than with INS and adjustments in our approach were needed.

There were a number of hurdles that we needed to overcome:

Some of our clinicians (both physicians and dietitians) did not have equipoise about protein dose.

Increasing protein intake was sometimes a response to deterioration in clinical status. Thus, a protocol with a fixed protein goal felt too inflexible to some.

To overcome this obstacle, we used the abbreviated slide deck from the EFFORT trial to educate our staff about the limited and conflicting existing data regarding outcomes associated with protein dose, ICU by ICU.

The slides also present the novel concept of embedding a RCT into an existing registry, an idea that excited clinicians about potential trials that they might initiate after learning from this experience.

Identifying only the high-risk patients to enroll was an adjustment from our prior INS experience.

Discussions with our ICU physicians.

Identifying patients who were likely to have prolonged ventilation was challenging in some situations despite close discussions with the ICU team. Patients sometimes remained intubated when the ICU team anticipated rapid extubation and other patients who were anticipated to have prolonged ventilation were extubated right after enrollment. After missing a couple of patients who ultimately met enrollment criteria and enrolling a couple of short-stay patients, we learned to observe patients in this gray area for an additional day to better determine their clinical course. Daily screening of the ICU census gave us the flexibility to monitor the patient’s course and enroll the target patients.

Setting up a system to collect data prospectively in order to adjust protein intake to ensure delivery of the goal was a new challenge.

We had also adopted a new electronic medical record (EMR) since our last INS participation, and needed to identify data fields. Furthermore, our nurses’ documentation of intake from enteral feedings was highly variable with the new EMR.

We had two graduating senior nursing students who volunteered with EFFORT in order to learn about clinical research. At least one of them came into the hospital every morning to collect enteral feeding volume data from the pump history and to confer with the bedside nurse about actual intake. They then compared this information to that in the EMR and sent an informative email to the ICU dietitian so that she could adjust the enteral orders as needed to deliver the goal.

As their final step, they created a procedures manual for future students that delineates in detail where to find each of the variables in our EMR.

Patient enrollment and data gathering takes time.

Because data collection is occurring prospectively and is likely to occur as part of routine clinical care, it is important for clinicians to build a process into their daily work flow. It may be helpful to begin data collection on a sample patient to more accurately assess the time commitment for each patient.

Daily screening for new patient enrollment can take 15-30 minutes; communication with clinicians and enrollment of each patient may take additional time depending on the complexity of the patient situation.

Once a patient is enrolled, baseline data collection, including APACHE II and SOFA score variables, can take 30-45 minutes.

Daily data collection of nutritional adequacy data takes approximately 15 minutes and is likely able to be completed during routine clinical care. There may be additional time required to communicate necessary changes in the nutrition regimen to the provider.

The efficiency of your site will be dependent on the availability and reliability of medical record data. Testing the process of data collection prior to patient enrollment will allow you to have a better sense of the time needed at your institution.

Key learning points:

Teamwork is needed to conduct a clinical trial, even when the data are embedded into a database with which you are familiar. Ensuring that the key data collectors have a process to follow and adequate time is the key to success.

The value of a project like EFFORT to experiential learning for students cannot be under-estimated. Their contributions to our data gathering were important, they convinced the bedside nurses that their data were meaningful to the trial’s success, and they advertised to the other students in their cohort the importance of nursing documentation.

Charlene Compher, PhD, RD | Marianne Aloupis, MS, RD | Jennifer Dolan, MS, RD

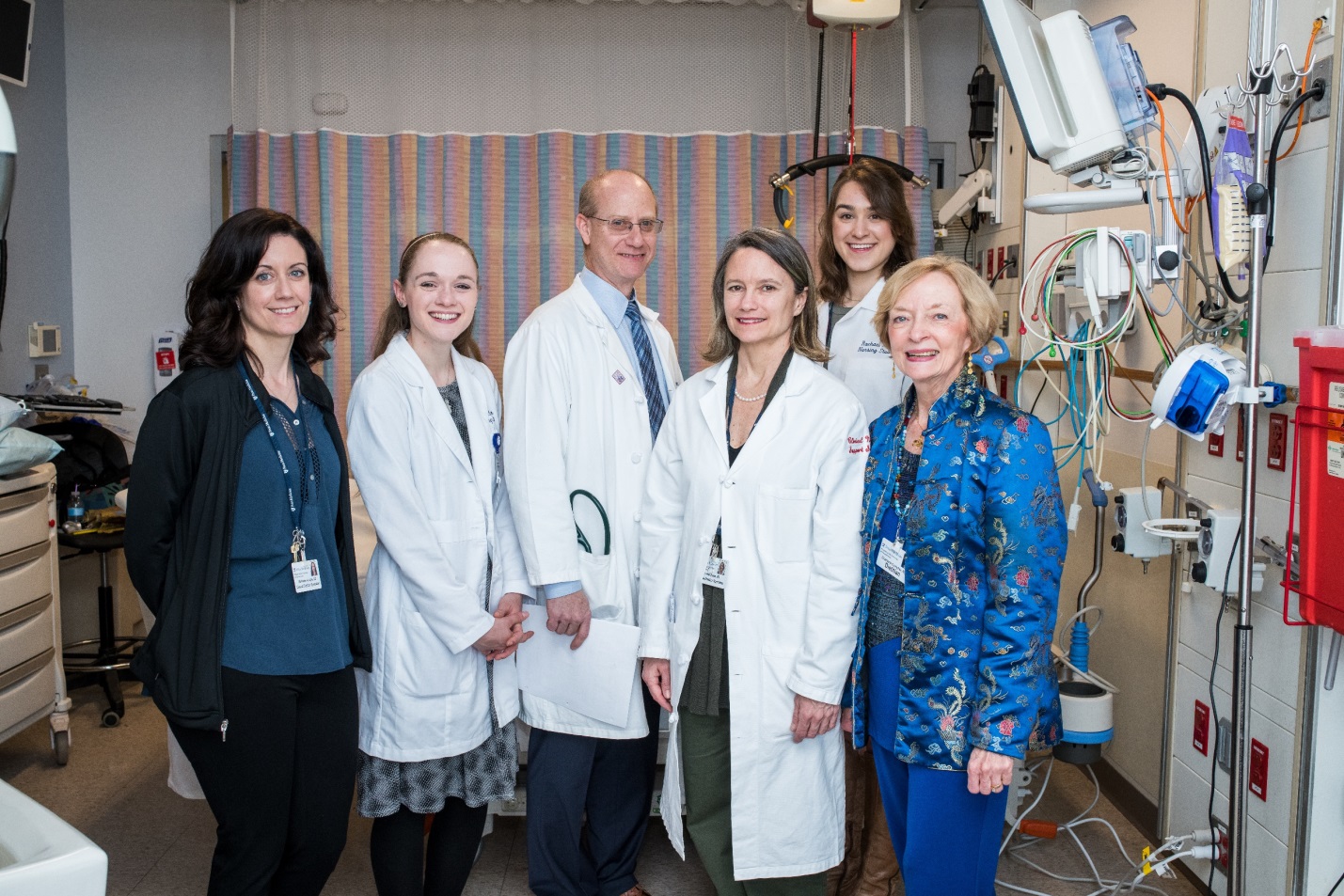

For the photo of the Penn EFFORT Medical ICU Team, from the left:

· Marianne Aloupis, MS, RD is an Advanced Practice Clinical Dietitian who coordinates quality assurance and research data for Penn’s Clinical Nutrition Support Service.

· Charis Anderson is now a graduate nurse who loved her contributions to the EFFORT trial because she learned so much.

· Barry Fuchs, MD, is the medical director of the Medical ICU who embraced the EFFORT project.

· Jennifer Dolan, MS, RD is an Advanced Practice Clinical Dietitian who leads nutrition care in the MICU.

· Rachael Peters is a graduate nurse whose first experience with research was on EFFORT. She values the organized systems and contributions that she can make as a nurse in her first ICU position.

· >Charlene Compher, PhD, RD is an Advanced Practice Clinical Dietitian and coinvestigator with EFFORT at Penn and with the trial overall. She came to doctoral education with a burning desire to develop the skills needed to use clinical data to answer important clinical questions, such as the best dose of protein for critically ill patients.